Finishing Touches

By Dean Torges

Our bows milled and ready to be braced, let's get to the business of

stringing them up. Before we begin, a word about our enterprise. Please

award as many of these following tasks to small hands as you can. Though

I coach them as instructions to you, you must in turn decide which of your

helpers can do what.

String

Number three braided Venetian blind cord (3/32 of an inch thick) makes

a quick and economical bowstring for kids' bows. Thick and soft enough

that it doesn't need to be served, it can be shot bare fingers. It stretches

with use, though, but we can compensate for that either by tying a timber

hitch on the bottom nook, or by making the top loop an adjustable knot.

Directions follow for the latter alternative.

To tie a quantity of these strings quickly, make a simple string jig by

pounding two 6d finish nails part way into scrap stock at a distance three

and one half inches shorter than the nock shoulders of the bows.

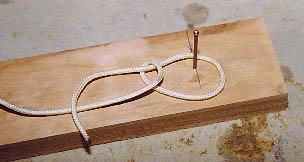

Cut the cord(s) 10" longer than the distance between the nails. Around

one nail, tie a small bowline so that it will fit snugly over the lower

nook.

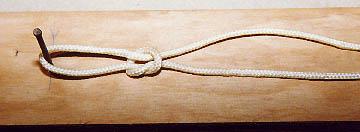

Stretch the cord to the far nail. Begin an overhand knot about 1 1/2"

short of this nail, then pass the tag end of the cord around the nail and

back through the overhand knot.

Snug up the overhand knot and tie a figure eight knot into the tag end

of the cord so it cannot pullback through the overhand knot.

You can shorten the cord when it stretches by pulling on the tag end of

the figure eight to decrease the loop and then retying it closer to the

overhand knot. If the loop grows too small over time, simply retie the

overhand knot further down the cord.

Tiller

We began this series on the premise that laminated staves make bow building

predictable. Several important principles derive from this premise, but

none more attractive to the tyro than the prospect of mechanical tillering.

"Mindless tillering" I called it-the prospect of arriving at

tiller fearlessly-no mumbo jumbo, no incense on the end of the work bench,

no invocation of inscrutable spirits, no guess work, no dumb luck. Self

bows must accommodate a stave's every aberration, nuance and undulation

in the tillering process, and therefore require a steady stream of decisions

and evaluations. Laminated bows glued up from clean stock come to tiller

with mathematical precision.

The reason is that the act of lamination makes wood homogeneous. This

homogeneity allowed Forrest Nagler, in “Archery: the Technical Side,”

to prescribe the exact measurements of width and thickness at intervals

of

length along a backed stave such as ours with the certainty that should

the bowyer focus upon arriving at these measurements, the result would

be a bow tillered to full compass, within certain weight limits as well.

I have seen bows made in obedience to these measurements, and they came

up fine bows indeed. Bows of consequence, by deference.

Our technique for tillering required much less attention to detail.

Its only prescription was a uniform taper from the handle area to the nooks.

If we tillered with a jointer and paid attention, the bows came off the

jointer table fairly well tillered. If we attempted the taper by hand,

say with a jack plane as shown in photographs in the preceding essay, chances

are good that the bow has flat spots or weaknesses in the tiller because

the layout was imprecise or because hand planing removed wood unevenly.

String up some bows and let's look at them.

The bow in the background with the uniform taper came that way off the

jointer table. The bow withy walnut handle riser in the foreground was

hand planed to pencil marks scribed on the stave's end.The top limb shows

more stiffness than the bottom limb. See how much closer the string comes

to the upper limb than to the lower?

Remedies to tiller are simple. Scrape or plane wood off the stiff areas;

stay away from hinged areas,sections of limb that bend too much. Stop removing

wood when the bow responds by forming a gentle arc in the braced position.

Don't worry about weight on these bows. They should end up under 20 lbs.,and

kids will know how far to pull them.

Handles

Time now to form a handle. A variety of possibilities are available to

you. For example, if you didn't glue on a riser, mark out about a four

inch section in the middle of the bow. Wrap it with drapery cord, anchor

it at both ends with upholstery tacks, and secure it completely by swabbing

the cord with a wash coat of glue and water, mixed about two parts to one.

Shellac or varnish it after it is dry. You may wrap a handle/riser combination

the same way, providing the young shooter a corrugated grip.

If you wish to fill out the grip on a bow without a riser, tear old

bed sheets or similar cotton rags into strips of random length in widths

about 1/2 inch. Soak them in a wash coat of glue, about 3 to 1,squeeze

out excess moisture and wrap them to form a grip in whatever shape you

wish. They will dry and hold their shape. Either shellac them as is, or

wrap them with cord, glue them down again and then shellac them.

Finish

Assuming that all sharp edges have been radiused, that the bow is tillered

and sanded and handled, it is time to seal things up.

Lots of possibilities exist for a quick, easy finish. Water borne varnishes

apply with a cheap disposable foam brush, dry quickly and are odorless.

Paraffin, as described in Chapter 9 of the bow series in Traditional

Bowhunter also works nicely. However, the paraffin must be hot to flow

into the wood, so the danger of small hands attracted to a hot, messy,

gooey task should be considered.

l would recommend shellac. Amber or white. Kids can swab it on with foam

brushes or wipe it on with a cheesecloth pad dipped into the can. In either

case, disposable latex surgeon's gloves help keep clean-up to a minimum.

Steel wool between coats and over the last coat to smooth the finish ski.

If your intention is to decorate these bows with patterns or figures, avoid

the paraffin finish. Shellac works better than varnish here. Lay down one

or two coats, sand them out lightly, and then use colored markers on felt

tipped pens for your artwork. If you try to draw on raw wood, the ink will

fuzz away from your lines, and it may bleed into the finish you choose

to cover over it. However, almost any felt marker works on the top of shellac.

|

Mitch Grogg and friend, with a hickory bow inspired by

Stickbow that he whittled and decorated himself. |

A word about shellac. If your crew has a tendency to glob it on, one coat

may be enough. Too many coats and shellac gets splotchy. Two coats with

a sponge brush, one followed by the second within 15 minutes, should be

plenty. Steel wool after the second coat has dried to smooth up the finish.Note,

too, that shellac has a shelf life. If yours does not dry within minutes

of application on a test piece,if it remains sticky, take it back to the

store for a refund.

Copyright 1997, Dean Torges